If the big bets from some of the world’s largest tech companies such as Meta and Apple come off, we’re on the precipice of a new technological age: spatial computing. Defined as “human interaction with a machine in which the machine retains and manipulates referents to real objects and spaces” (Greenwood, 2003) spatial computing is potentially the “next big thing“, and represents a quantum leap from today’s applications of virtual and augmented reality made possible by development of better sensors combined with higher fidelity visual, aural and haptic feedback devices.

Apple announced a project that it has reportedly been working on for many years at this year’s Worldwide Developer Conference, the Apple Vision Pro. While the world waits for its limited release next year, developers have been given a preview, and many details have been made public that suggest the potential applications in education. What can we expect, and how can we prepare for designing learning experiences with such a radically different interface? Let’s take a look at a few ideas.

The Promise of Spatial Computing

One of the key ideas of spatial computing is linked to a frustration we often experience with the predominance of screen-based interaction: we are forced to work in a way that ties us to a physical location, experiencing the world in a highly constrained way. A screen might be large, but if it is, it’s pretty heavy and it’s usually sitting on a desk or attached to a wall. If it’s small, like a phone, it can come everywhere with us, but we’re forced to view everything through a keyhole. We’re so used to doing this, we barely notice, but it is difficult to deny that there are significant ways our typical devices radically shape our lives, not just ergonomically but socially.

Spatial computing, at least in its advanced form, promises to improve this situation by effectively making the technology layer closer to our everyday experience. The idea is that the sensors and feedback are so subtle and sophisticated that we genuinely feel like we’re experiencing digital content alongside the analogue world in an uncompromising way. Have you ever put on a virtual reality headset and noticed lag, felt disorientated or nauseous, or experienced the jarring sensation of touching something in the real world that snapped you out of your virtual experience? Spatial computing aims to do better.

You will soon be able to attend a world-class live event like a concert or sporting fixture and genuinely feel like you are there. Not just sitting in the stands, of course — you might view things from a first-person perspective, flip to a drone view, or superimpose stats on a real-time field. A lot of the elements are already in place in mixed, augmented and extended reality devices now. Spatial computing can bring these together into a coherent experience.

Spatial Computing and Higher Education

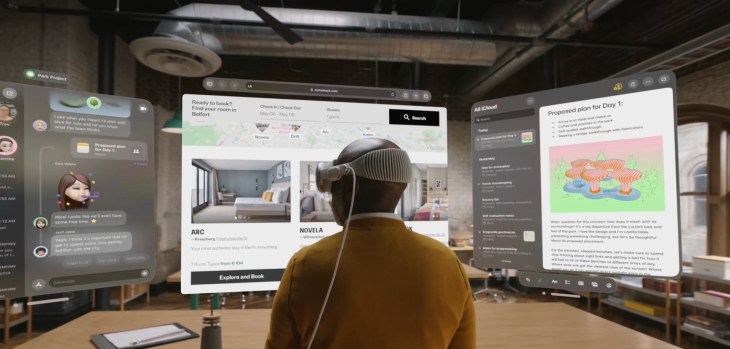

How might a device like the new Vision Pro, or whatever comes after it, be applied to higher education? Firstly, let’s take a look at the first generation design of the device that Apple announced earlier this year, and then the different ways it can be used educationally.

The Vision Pro looks something like a pair of ski goggles, with a continuous front panel that acts as a lens, and includes an external display. This display allows a feature Apple calls EyeSight — a live visual of the wearer’s eyes. The idea is that the headset appears almost translucent to someone in the same room, enabling real time in-room interaction even while using the device.

The device is constructed using a total of 23 sensors, including a dozen cameras and six microphones. IR cameras inside the Vision pro track your eyes, downward-facing cameras track hand movements, and Lidar sensors track the position of objects around you.

The headset’s power source is an external battery pack that provides up to two hours of use, and you can avoid this if you are somewhere you can plug into power. Most of the power is to drive the OLED panels, which deliver more pixels than a 4K TV to each eye.

Spatial Personas

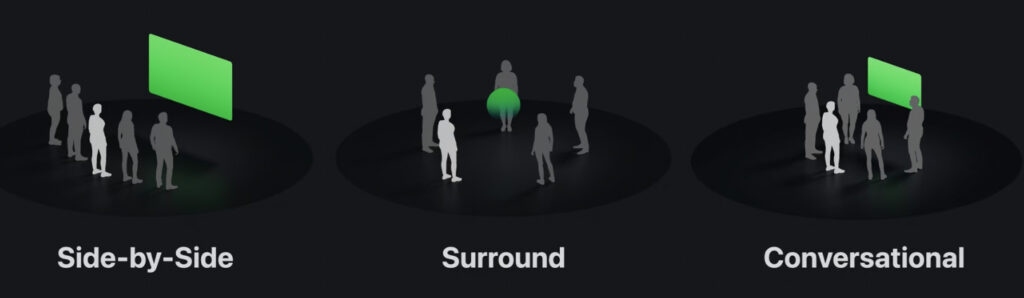

Developer documentation reveals that the device supports a range of interaction modes (or “spatial personas”). One of the core design principles that Apple espouses with VisionOS is the idea that interactions between people should allow natural expression, meaning you can look people in the eye, convey things with body language, and undertake shared activities. This is welcome news for learning experiences. But what will it look like, and how will it work?

Firstly there is the idea of bringing remote users into the same room, as though you are sitting next to them on the couch. So from your perspective, if someone is sitting to your left, from their point of view, you are sitting to their right. The device keeps track of all of this, giving you a slightly different experience from the others in the room, and allows for freedom of movement and clarity on who is taking each action, such as controlling a video. People can feel a sense of physical presence, in a way that is sometimes missing from online interactions, and drawing on our experience of shared real-world interactions.

When you join a shared experience (Apple calls this SharePlay) on the Vision Pro, there are various templates that determine the seating arrangements for those joining. So as well as being side-by-side, your group may surround an object or may be arranged in a circle to promote conversation.

Thornburg’s four spaces

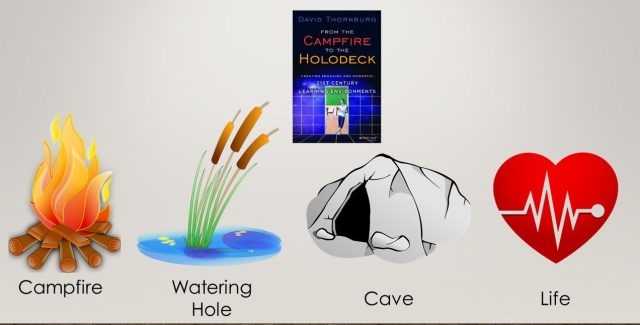

David Thornburg presciently invoked Star Trek’s Holodeck around a decade ago when writing about the ultimate redesign of spaces to support a balanced range of learner needs. There is the “campfire”, representing the lecture theatre or seminar room, the “watering hole”, which is the social learning mode where people meet to converse, the “cave”, where we can focus on meaning-making and writing, and finally there is “life”, representing experiential learning, where learners apply what they have learnt to real-world activities.

It is possible to imagine how spatial computing could allow the Holodeck ideal if we can design compelling learning experiences well enough. Let’s imagine, for example, that we want to design an experience where MBA students undertake a real-time simulation of a corporate crisis. Just as we would in a learning management system, we could predetermine a number of contextual elements — the roles students will play, the back story of a company its situation, and shoot some videos of the main characters at various points in the simulation.

Learners might be invited into a side-by-side experience to be briefed by facilitators or view videos that set the scene or introduce complications at various points. They might separate into smaller groups and work together in another side-by-side setting, for example, to develop a group response to a crisis. In another context, they may need to enter a meeting to discuss what to do next. These sorts of simulations are often conducted in real-world environments, sometimes fitted out with elaborate video set-ups to evaluate learners’ work along the way. However if we can do them in a compelling enough shared environment, learners can be anywhere, and their experience might presumably be recorded for later feedback and evaluation.

Accessibility Implications

Careful thought always needs to be put into how learning experiences can be designed in a way that is universally accessible, from the ground up. Apple deserves praise for building impressive accessibility into its operating systems and its devices, and thankfully the Vision Pro appears to be thoughtfully designed with this philosophy, although we will need to wait until the release date to see how this translates into real-world applications. What we know now is that this means controls can be personalised, including volume levels and captions, language preference, and other contextual elements. If all participants are using the Vision Pro with their own accessibility settings, there is the potential for a more level playing field. However, some serious questions remain about the accessibility of the technology, for example, the steep entry-level cost, at least for now.

About the author

I am an independent consultant focusing on improving learners’ lives using emerging educational technologies and learning space design (physical and virtual). If you would like to book a 30-minute consultation, please visit my website: RocketShoes.io.